I'm sure the heavy snow that began early in the morning of December 27, 2014 in Oklahoma was a surprise to many; an event which could've led to more significant impacts than what we saw given that it occurred only 2 days after Christmas .

Was the snow event really as surprising as implied, and if not was there a way to effectively communicate a seemingly low probability event like this? In this day of exceptional numerical weather prediction, we shouldn't have seen a dry forecast just 12 hours before 3-6" of snow fell along the I44 corridor. So the question is, was there no indication that a snow storm was on its way during the previous evening?

A scene typical of central Oklahoma roads. Unknown source.

Storm total snow amounts courtesy of NWS Norman.

When the snow began to fall in thin bands as the radar image showed it appeared that an elevated frontal circulation was possibly involved. The 700 mb frontogenesis analysis in the SPC meso analysis plot helps support the idea, with the best values nicely lined up parallel to the snow bands observed by radar. This is important because the model guidance should have a similar signature in the forecasts.

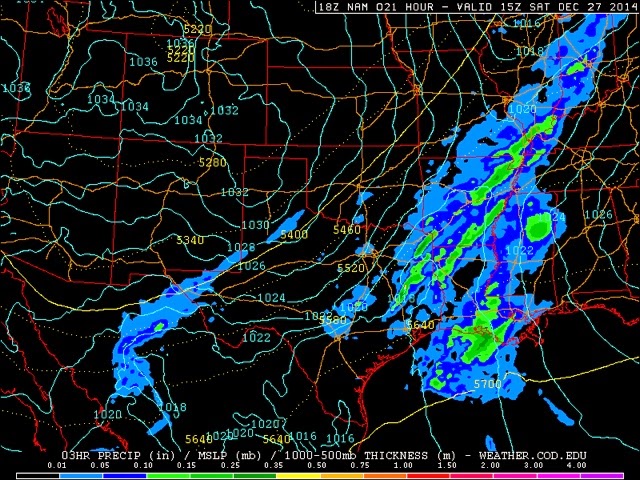

The NAM forecast model, however, didn't show much of any precipitation from the previous evenings run. What it did show in the Texas panhandle, however, appeared to be aligned in a similar direction as the frontal bands observed the next morning. But the NAM was as dry over central Oklahoma as the forecasts.

The NAM 15 hr forecast valid Dec 27 of 3 hour precipitation courtesy College of Dupage

The GFS evening model run, however, showed a slightly wetter pattern as a band of three hour precipitation accumulation appeared in roughly the same orientation and placement as was observed. The amounts were not quite up to the observed values but it's orientation gave a clue that it was on the right track that something may have fallen out of the frontal circulation aloft and that possibly an inch of snow may fall by late morning the next day. The only problem was that this GFS forecast was available only after the evening news cycle was completed, thereby limiting its usefulness for planning in the evening before the event. Was there information in the guidance that could've been made a bit earlier?

Well, possibly. In the afternoon before the snow day the short range ensemble forecast system, or SREF, showed that a several of its 15 runs forecast over one inch of snow in a corridor quite similar to the bands observed the next day. The probability of at least one inch of snow was only up to 20% in the college of du page model output but the SPC plume diagram valid for Norman showed that the several runs depicting the snow were very similar in timing and amounts. At least this output should give one pause that something may happen.

The SREF probability of 12 hour snow exceeding 1" valid 18z Dec 27 courtesy of the College of Dupage.

By 9:30 pm the evening before, three successive runs of the HRRR (high resolution rapid refresh) model were available that showed an axis of snowfall accumulation approaching or exceeding 1" right over the I44 corridor into the OKC metro area. The hourly model runs allows its users to assess the consistency of its forecast. When three runs in a row showed a similar forecast then the likelihood of accumulating snow may not have been so improbable.

The HRRR total snowfall at forecast hour 15 for the 23 z Dec 26 and 01 z Dec 27 runs courtesy of NOAA/GSD.

So the big question of the evening was whether or not the guidance provided enough confidence to forecasters to go with some kind of winter weather warning. In the NWS, forecasters are provided with a set of guidelines on when to issue winter storm watches, warnings and winter weather advisories. The NWS could've issued a winter storm watch, however they would need a 50% chance that winter precipitation would actually fall and accumulate to create hazardous travel conditions (see the directives at http://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/sym/pd01005013curr.pdf). However we could debate for a long time whether or not there was a 50% chance based on the available guidance. One forecaster may consider that there needs to be a 50% chance that a winter storm warning criterion snowfall occur while another may not. I believe no one would argue that the chances of 4" or more accumulation was nowhere near that 50% value. Yet the directives suggest that a local forecast office has great latitude in determining the criteria for issuing a winter storm watch. Having snow falling enough to cover roads at rush hour would certainly be a good reason to consider sliding the threshold downward. But this is a judgement call and the uncertainty in the guidance is enough that I can understand a forecaster decision not to issue a winter storm watch.

No watch was issued for this event, but perhaps because a forecaster considered the chances of winter weather to be at 20 or 30%. With those low, but not negligible odds, What kind of message did a forecaster have available to advise the public? A hazardous weather outlook could've been issued. However those kinds of products are usually reserved in the day 3-7 lead times. A special weather statement could've been issued since its format provides enough flexibility to provide a variety of information. Perhaps then the statement could've been backed up by reposting to newer avenues of communication such as online briefings, social media and nwschat. Typically these avenues are reserved for winter events with a higher confidence forecast.

Communicating a heads-up about low probability events is commonplace in convectively induced severe weather events but not for winter weather situations. Yet in the plains states, and other places, high impact events are often dominated by mesoscale processes (eg. Frontal bands, cold frontal squall lines), as this event demonstrated. These events are going to be more difficult to forecast, and therefore, lower confidence of occurring as anticipated for any one spot, much like summer convection. Thus the communication required to warn for the potential impacts have to be different than the synoptically dominated snow storms for which the traditional avenues of communication are intended. The challenge is when and what to communicate with these lower probability but potentially significant events.